Return to Oz

1985|Walter Murch

Dorothy Gale follows the crumbled remnants of the yellow-brick road to the Emerald City of Oz. Shot from a low angle that foregrounds the disturbed bricks, she is a solitary figure dwarfed by the ruins around her, a subject in her own fractured fairy tale. This troubling sight is only a hint at the horrors Dorothy will find as she makes her second journey through the magical land. It’s an Oz quite unlike the one she (or the viewer) remembers, one bereft of color, music, and cheer.

The film opens six months after the tornado of the first story leveled the Gale family’s farm. Still struggling to pick up the pieces, Aunt Em (Piper Laurie) is equally concerned with Dorothy’s (Fairuza Balk) persistent nonsense about talking scarecrows and ruby slippers. Her solution, bewilderingly, is to wipe these pesky fantasies from the child’s mind through experimental electro-shock therapy. What follows might have been lifted straight from a child’s nightmare, as Dorothy is left overnight at a remote clinic, carted to a creepy operating room while the screams of unseen (presumably grown, male) patients reverberate throughout, and chased through a rain storm by a devious nurse before escaping down a flooded river on a makeshift raft.

It comes as a great relief, then, when Dorothy wakes up the next morning to find that the river has transported her back to the wonderful land of Oz. But her joy is short-lived when she discovers Oz’s current condition. What was once a thriving paradise is now a vast wasteland, and most of its inhabitants (including old friends the tin man and cowardly lion) are turned to stone. Oz is now under the rule of the evil Nome King (Nicole Williamson), a shape-shifting rock spirit who lives in a rather hellish underground cavern. Aiding him in his widespread destruction is Princess Mombi (Jean Marsh), a sorceress with a collection of 30 severed heads (to which she plans to add Dorothy’s) that she can switch out with her own as she pleases.

If you think this sounds like a sick joke, you’re not alone. When Return to Oz was released in 1985, it was savaged by critics for its nightmarish treatment of the beloved L. Frank Baum stories. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert fell over themselves ripping it to shreds on their TV program. Leonard Maltin gave a more restrained but still damning review, calling the film “a bummer” and “joyless.” He was right, of course. Return to Oz is indeed a joyless bummer, a shockingly depressive work for one ostensibly aimed at children (and produced by the House of Mouse to boot). But what no critic seemed to consider was why this necessarily made it less of a movie.

Return to Oz is the directorial one-shot of celebrated sound/film editor Walter Murch, whose résumé includes groundbreaking work on The Conversation (1974) and Apocalypse Now (1979). He seems to have brought to his Oz adaptation the very adult sensibilities that characterized Hollywood cinema in the pre-Star Wars 70s, drawing little nuggets from Baum’s original texts (The Marvelous Land of Oz and Ozma of Oz, specifically) and fashioning them into a somber rumination on loss and isolation.

Little Dorothy is presented as a perpetually secluded figure. From her first moment onscreen, staring blankly at the night sky through her bedroom window, she seems totally disconnected from her surroundings. Over the course of the movie, she is repeatedly locked away, either by force or of her own will. Even the new group of misfit and patchwork friends she makes this time around does little to dispel the notion that she is basically on her own, as for much of the film’s length, Fairuza Balk is the only human actor onscreen. Her quest is driven largely by a need to find a sense of belonging and stability, not unlike Judy Garland’s desire to find her place “over the rainbow” in the 1939 film. But home is not so patly realized in Murch’s vision. With Dorothy’s Kansas life and her dream world both in disarray, she is forced to assume an adult role in restoring order (it’s no coincidence that one of her new friends, Jack Pumpkinhead, calls her Mom).

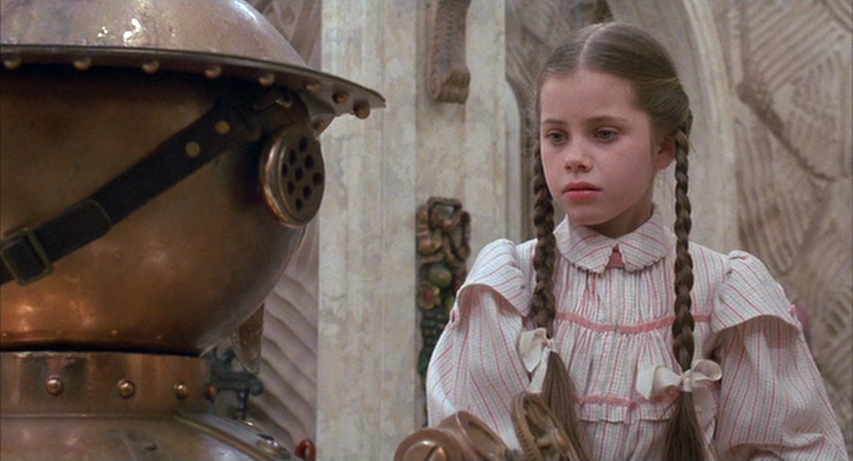

The casting for Dorothy is essential, and nine-year-old Fairuza Balk perfectly exudes the innocence as well as the adult earnestness of her character. There’s an innate sadness in Balk’s voice and demeanor, and it’s not surprising that she made a career playing disaffected youths. In his TV review, Maltin bitches that she never smiles until the end of the picture, but that’s not her job here. She is not your average plucky child-heroine who makes cutesy faces and spouts bad one-liners. Murch takes the child seriously, just as children take themselves seriously, and her problems are no less harrowing than those of any adult.

One of the truly unnerving things about Return to Oz is the way in which Murch subverts our expectations of an Oz sequel. Unlike its 1939 predecessor, this is never a “pretty” movie to look at. It’s as visually drab as the earlier film was visually brilliant. In place of Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg’s chirpy song-score are David Shire’s melancholy strings. And apparently recalling his work on The Conversation, in which he distorted the titular exchange to sound both mechanical and otherworldly, Murch had his sound designers apply a strange echo effect to most of the film’s dialogue, enhancing our sense of loneliness by making the characters sound distant and engulfed by empty space.

Perhaps nothing dashes our memories of Oz, however, like the sight of Nicol Williamson’s Nome King hiking up his regal robe to reveal that he is wearing the ruby slippers. To see the sparkly footwear (for which Disney paid MGM a hefty fee) fitted snuggly on the feet of this gruff, bearded figure made entirely of rock is to witness a delirious perversion of one of American cinema’s treasured images. (For a little added perversity, read up on some of the Freudian interpretations of the 1939 movie and then come back to this scene.)

But like all children’s fantasies, this one ends in triumph for our heroes. While it’s comforting to know that order is restored in both the real world and Dorothy’s dream world, the line between the two is never clearly drawn. There’s an uneasy ambiguity as to whether Oz is a real place or a product of Dorothy’s imagination. In Baum’s original works, to which this movie closely adheres, Oz is very definitely real. In the 1939 film, it was all a dream. But Murch’s vision occupies murkier ground, one where Oz/Kansas doppelgangers may suggest either Dorothy reconstructing her reality through her dream or the powers of Oz seeping into the ordinary world. Viewers are free to make of it what they will, but I like to think that Oz exists only in the dream, and that Dorothy’s real victory is being allowed to keep her fantasies.

— Felix Gonzalez, Jr.

CAST: Fairuza Balk, Nicol Williamson, Jean Marsh, Piper Laurie, Matt Clark, Emma Ridley

COUNTRY: USA

No comments:

Post a Comment